I have lived in London most of my life, and one of the pleasures for me in researching and writing The Favourite, an exploration of the relationship between Elizabeth I and Walter Ralegh, is that so much of their story is also a London story. Or, more accurately, London is always there in the background, discreetly attracting my attention with its prodigies. I am forever tempted to go in search of it.

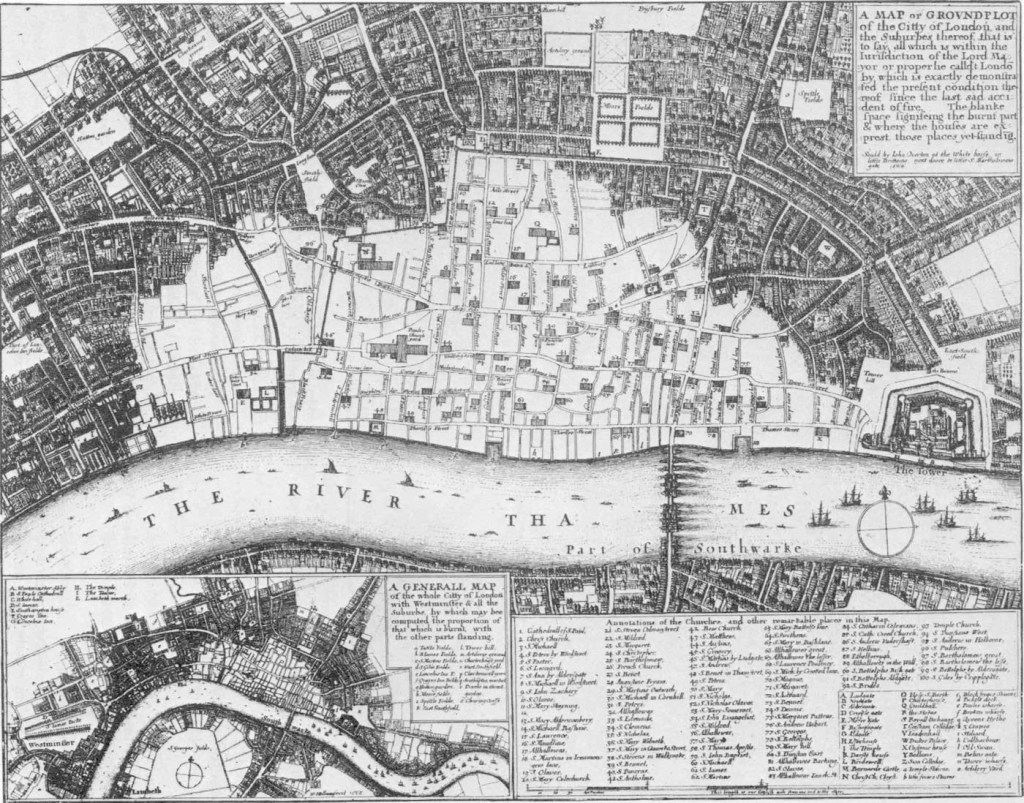

Of course, Ralegh’s London no longer exists, precious little of it having survived the Great Fire of 1666, although the Victorians also contributed along the way, destroying Ralegh’s Islington home, for instance.

But the extent of the fire’s devastation is still unsettling; eye-witness descriptions are reminiscent for the modern reader of footage of Hiroshima or Dresden. In the aftermath of the fire there was ‘Nothing but stones and rubbish… from one end of the City almost to the other’ wrote one Lincoln’s Inn lawyer, while a man from the bleak lunar hills of Westmoreland found himself gazing upon a ruined reflection of his home: ‘The houses are laid so flat to the ground that the City looks just like our fells, for there is nothing to be seen but heaps of stones’.

Despite having read such comments many times before, I was nevertheless stunned to sit in the library and look for the first time at Wenceslaus Hollar’s ‘before and after’ maps of London. Those of the City before the fire, in common with the maps and drawings of his predecessors like Visscher and Agas, are profligate with detail: they provide not merely a street plan but also a bird’s-eye view of the city from some notional perspective in the air.

Along each street you can see something of each house, even if often it is only the pitch of the gabled roof or the number of floors, windows flecked with ink; behind the houses are a patchwork of courtyards, paths and gardens studded with trees. It is impossible to know to what extent these kind of details are intended as accurate representations, as opposed to the merely illustrative or emblematic, but they are nonetheless vivid testimony to the profusion of buildings in Tudor and Stuart London, and to life lived, in a lovely Elizabethan word sadly fallen from the language, ‘pestered’ close together – meaning overcrowded, clogged, pressed against one another. That ‘pestered’ also seems to imply of pestilence and plague – despite being in fact derived from a different word-root – adds a poignant undertow to the image of these packed and compact lives.

Wonderful ! I now want to walk the whole area….

Fascinating. Thank you.

Terrific article. Thank you.

Wonderful post, Mathew. It is great to know that another soul finds a similar joy in reconstructing historical landscapes – though you are much more eloquent than I in doing do. Well done!

Fascinating article – thank you for posting it here.

Thank you for making this post available and puting the link on twitter. The love you have for your city and her river, shone through and captured my imagination. It was a real treat to read. Well done Mathew, thouraly enjoyed it.

George.