The Roma are an Indian people. They left what is now north-west India and Pakistan in the early decades of the 11th century for reasons which will likely never be known, but which may relate to incursions by Muslim armies in the region. They moved west around the Caspian and into the Byzantine Empire by the end of the 13th century. Their arrival in Europe can be traced through city chronicles: by 1362 they were in Croatia, by 1401 in Poland, by 1418 in France, and so on.

This might seem a blandly unremarkable statement of fact, but, like much of Roma history and culture, it has often been contested by people outside the community. Initially derived from linguistic study of the Romani language group, the idea of Indian origins was widely derided by late 20th-century sociologists and ethnographers, who argued that Roma identity was merely a construct of dominant social groups, a colourful way of labelling indigenous outcasts and vagrants. And if the Roma themselves rejected the suggestion, well, they would, wouldn’t they? “The intelligentsia in Gypsy circles are not likely to profit much by challenging the core concepts of Gypsy studies,” scoffed Dutch sociologist Wim Willems in 1998.

But if DNA research has now confirmed what Romani scholars had long argued, there is no shortage of other misrepresentations to go round. It is only two years since Matthew Parris could write in his column in The Times that the Roma and other travellers were “not a race but a doomed mindset” and that society should work to eradicate their way of life. Of course, legislators have been trying to do that one way or another for centuries: the first attempt in England – in the form of banishment – is in a statute from 1531. Between 1551 and 1774, the Holy Roman Empire passed some 133 laws with a similar aim.

This April, meanwhile, Diane Abbott, the former Labour Party Shadow Home Secretary, wrote to The Observer that ‘Travellers’, as well as Irish and Jewish people, had experienced prejudice in the past, but not racism. “At the height of slavery, there were no white-seeming people manacled on the slave ships,” she concluded.

But for some five hundred years Roma in parts of Eastern Europe, principally Moldavia and Wallachia, were indeed enslaved. Punishments included having the soles of the feet beaten with a specially designed bullwhip until the flesh hung in shreds, or wearing an iron band around the necks lined with points, so they could neither move their heads nor lie down to rest. Roma women were raped, the men castrated. The killing of Roma slaves, technically illegal, was widespread but unpunished. Slave auctions continued until the 1850s, the decade that freedom came.

Another irony is that for centuries, the Roma were also denigrated for the blackness of their skin, as Klaus-Michael Bogdal amply demonstrates in Europe and the Roma: A History of Fascination and Fear. They were “blacks…wild ugly Africans or Moors”, according to Swabian annals of 1418. “The men were very black and… the women the ugliest and darkest-skinned people anyone had ever seen,” runs the Paris city chronicle of 1427. In 1909 a Danish travel writer could refer to “The Gypsy… with his alien head shape and his black skin… [which] together with their furtive movements and shameless gesturing gives them a resemblance to apes”.

And then the Roma were also, like the Jewish, a target for Nazi genocide. Estimates for the numbers murdered vary, but it might be as high as 1.5 million – around half of the Roma population of Europe at the time. Fewer than 5,000 Sinti – the Roma community in Germany – survived, Bogdal writes; some 1,500 survived from the 25,000 transported from Romania. To distinguish their suffering from the Holocaust, Roma have started using a Romani word, porrajmos, to describe it. It means ‘the devouring’.

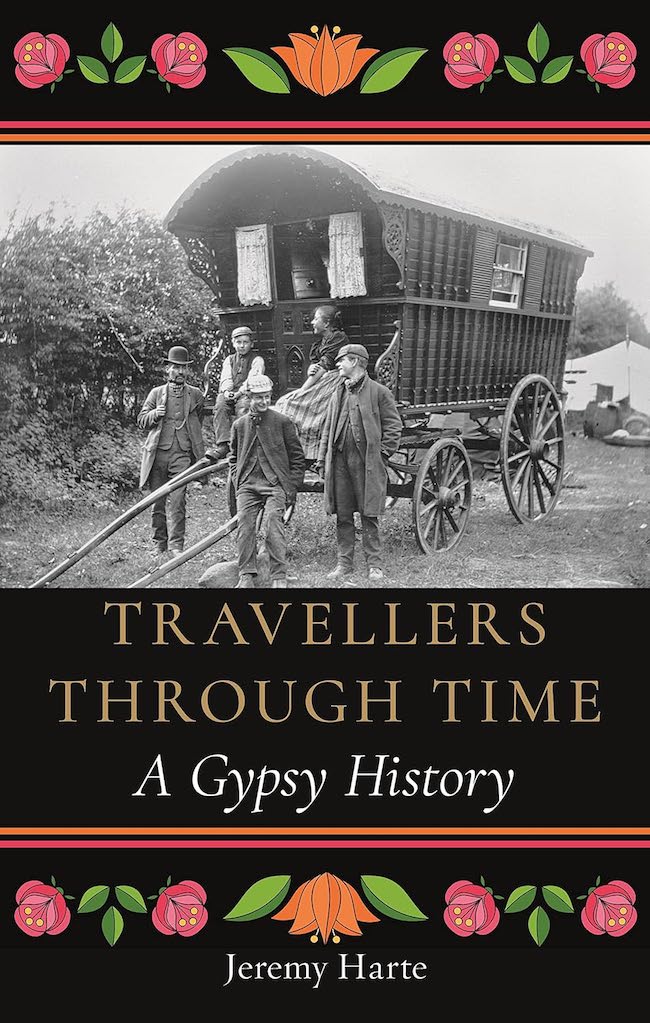

Bogdal’s is one of two new books that seek to explore the place of the Roma themselves, and Roma history and culture, in the wider society. The other is Jeremy Harte’s Travellers Through Time: A Gypsy History. Whereas Bogdal’s canvass is pan-European and his focus on representations of the Roma in the culture, Harte’s is local and English, and an attempt to examine the community from the inside.

It would be comforting to think that the porrajmos was the culmination of race and other hatreds directed at the Roma in Europe, but it isn’t true. Sterilisation programmes continued on both sides of the Iron Curtain, in Czechoslavakia and Scandinavia, into the 1960s. Soviet policy was to force the Roma into settlements and impose labour roles – policies remarkably similar to the enforced assimilation attempted by Austro-Hungarian Empress Maria-Therese in the mid- to late-18th century. Across Europe today, the Roma are both the largest – they number some 12 million people – and the most excluded ethnic group: nearly half live in “severe material deprivation” with fully 80% at risk of poverty, according to a 2021 survey from from the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights. Less than half of Roma children attend early education; only one in four completes secondary education. A UK report came to similar conclusions earlier this year, something which should surprise no-one but yet seemingly did.

Bogdal’s book ought to be the definitive account of these hatreds and of the people at whom they are directed. It has the ambition to be so and it contains much interesting material. It is, however, deeply flawed. It was first published in Germany in 2011 under the title Europa erfindet die Zigeuner – loosely, ‘Europe’s Invention of the Gypsies’ – a title which better reflects the contents than the English edition.

Presented chronologically, it is largely a literary survey of cultural stereotypes, summarised on page 280 – roughly half-way through the book – as “foreign nomads… a people of fortune tellers, thieves and robbers, musicians and dancers, whose beautiful women awakened desire”. An exploration of those tropes might have been worthwhile, but Bodgal’s method is to work through text after text with laborious plot summaries. Typically these are of works by minor writers, although some are minor works by great ones, Cervantes, Tolstoy and Strindberg among them. If you are in the market for a six-page précis of Archim von Arnim’s novella Isabella of Egypt, Charles V’s First Love, or a five-page one of Mérrimée’s Carmen, then this is the book for you.

Bogdal argues that the emphasis on literature is vital because “it is only through close textual analysis that we can go beyond the conclusions of history or sociology”. Unfortunately, on the basis of this book at least, the reverse is true. Roma history isn’t so much obscured here as displaced. Roma slavery is only mentioned in passing for example, and, somewhat surprisingly, Bogdal questions the historicity of organised gypsy hunts – heidenjachten – in the Netherlands and the southern German principalities in the 18th century, although most historians consider them a well-attested phenomenon. Becky Taylor, for instance, in Another Darkness, Another Dawn: A History of Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (2014) records around 100 deaths in the German hunts – although she also notes that the locations of the hunts were tied “very specifically to their role in providing labour for the armies and galleys of Europe”.

Bogdal would argue that the book isn’t about the Roma per se, but the representation of them in the dominant culture, but the result of that is that the Roma largely appear in these pages as ciphers for the fantasies – malignant, benign sometimes celebratory – of others, rather than as individuals, families and groups with agency and choice. Why write a book about the Roma in which “[the] main protagonists are the scholars, intellectuals, writers and researchers” whom Bogdal reifies as “the creators of culture” – a revealing insight into how he thinks culture works.

Bogdal’s account seems almost to occupy an imaginary, conceptual space at some distance from reality. Unless you establish some sense of what Roma life and culture was or is like, the cultural characteristics he identifies become abstractions – mere literary tropes – whereas surely the whole point of the book is the way these tropes were (mis)applied to living, breathing human beings with agendas and agency of their own.

The chapters on the 20th century are far the most successful in the book. We largely move out of the library and into the world, and the correlation between the literature, and in particular racist pseudo-scientific literature, and the lives of actual people comes into focus. These are the most tragic chapters too.

We see, for instance, that having been murdered by the Nazis on the basis of their ethnicity, the Roma were denied compensation by German courts in the decades after the war because their persecution was deemed to have been “‘preventative security and criminal’ measures taken to control ‘primitive ur-creatures’”. At one point the Munich Institute of Contemporary History debated whether “internment in concentration camps… led to an improvement in their behaviour”, a question which Bogdal rightly observes, was “based on an unbelievably false premise. Concentration camps were in no sense correctional institutions”.

The psychologists Robert Ritter and Eva Justin, whose work on criminality and race was used extensively by the Nazis to send Roma men, women and children to their deaths, never faced trial after the war. Indeed, their careers prospered. As Bogdal notes: “it was precisely the modern academic disciplines… that devoted themselves to social process… and followed scientific paradigms which encouraged and legitimated policies of discrimination, exclusion and extermination.”

Jeremy Harte’s book, meanwhile, provides something of a corrective to Bogdal’s approach. Travellers Through Time is packed with real people leading rich, complex lives. It is not, however, as its publishers claim, “the first complete history of the Romany people, from the inside”, both because Harte, while active in Roma archival and historical organisations, is not himself Roma, and also because it focuses almost exclusively on the communities in Surrey and neighbouring counties.

It is an approach with much to recommend it. As Harte writes: “Gypsy history must be a history of life as it was lived, not just the bleak outlines traced by official documentation, and to do that it helps to view things up close.” But that word ‘complete’ is doing an awful lot of work.

Those caveats aside, Travellers Through Time is an excellent and empathetic work of social history. Harte traces Roma history within his remit well, from their first arrival in the early 16th century, through the ebb and flow of persecution, tolerance and acceptance. In Britain, as on the continent, anti-Roma legislation was ferocious. An Elizabethan law of 1563 made it a capital offence not simply to be an ‘Egyptian’, but to look like or speak like one too. It stayed on the statute book until 1783.

Harte finds no executions under the act in Surrey, however, and only four in Middlesex. He notes that David Cressy, in his Gypsies: an English History (2018), found no more than several dozen deaths nationwide. (The last was in 1628, when 13 were hanged at a particularly bloody assizes in Bury St Edmunds.) This disjunction between rhetoric and reality is one of the reasons Bogdal’s literature-first approach is so flawed.

Romani culture has always been essentially an oral one, and where the Roma appear on the historical record, therefore, it is usually because of formal necessities such as births, deaths and marriages, or dealings with the law. This has often been taken as an affirmation of the accusations of dishonesty that have hounded them for centuries, but Harte doubts that they are over-represented in criminal cases. He has done an excellent job of sifting the parish archives, legal archives, and later those of the print media, to show how the Roma lived in, and how their lives were interwoven with the wider social and cultural economy.

He is particularly strong on the daily lives of his subjects, the nuances of routine. It is far from true, for instance, that the Roma were necessarily entirely itinerant. One 19th-century family recorded visiting 41 towns over the course of a year, but by that time many families only traveled through the summer and autumn, when the demand for seasonal labour was at its peak. “The gipsies are the best workers in the hop-gardens,” The Times reported; but farmers welcomed them too when it came to pea-picking, hay-making, bringing in the harvest, the holly season when wreaths were made to sell in London, and other tasks.

They were chimney sweeps, knife-grinders, tinsmiths. They repaired cane chairs, mended china; they made clothes pegs, clotheslines, baskets; they picked wild violets and primroses and sold them. “All the most popular Gypsy crafts had this in common,” Harte writes. “They took some wild resource which could be gathered for free and turned it into a saleable item.” Two-thirds of them described themselves as hawkers. All the family worked. Harte suggests each might have earned £1 a week this way, which compares favourably with a Surrey labourer’s typical earnings of 12s to 15s.

It is certainly true, though, that the arc of the story that Harte tells tends towards greater restrictions, greater limits on freedom of movement, on the kinds of trades practised. The 1822 Vagrancy Act, for example, legislated three months in prison for fortune telling; it is hard not to sympathise with the Victorian Roma woman Harte quotes: “If there [were] no fools, there would be no living.” The Highways Act of 1835 made it illegal for the first time to stop by the edge of any highway. As democratic accountability grew, particularly at a local level, so did the punitive sanctions.

Travellers Through Time comes with a glossary and the text is sprinkled with Romani terms – most commonly gorjer for non-gypsy. It’s a practice that some might find condescending, but it is on balance an effective way of reminding the reader this is intended as a history from the inside out, with Romani life as the norm.

If David Cressy’s book remains the definitive history tout court, Harte’s work feels like a good place to begin the work of rethinking attitudes like those expressed by Matthew Parris and Diane Abbott. Mobility and migration are sure to be among the defining social issues of European and global politics in coming decades. Is it too much to hope that, after six centuries, we might finally listen to, adapt to, and respect this great migrant, often mobile, people in our midst?

This is a greatly extended version of a piece that first appeared on Engelsberg Ideas in July 2023.