Death in the Victorian capital of the British Empire was problematic. “London graveyards are all bad,” the Board of Health reported gloomily, “differing only in degrees of badness”. There were 200 of them covering some 218 acres, yet by 1842 they were having to absorb over 50,000 new residents a year. “A London churchyard is very like a London omnibus,” joked Punch magazine. “It can be made to carry any number.”

Except, of course, they couldn’t. In 1845 a campaign group sprang up, the Society for the Abolition of Burial in Towns and, after a major cholera outbreak in 1848, the government acted. The Burial Act of 1852 effectively closed the existing churchyards. It was, the Illustrated London News wrote, “the embodiment of foregone conclusions”.

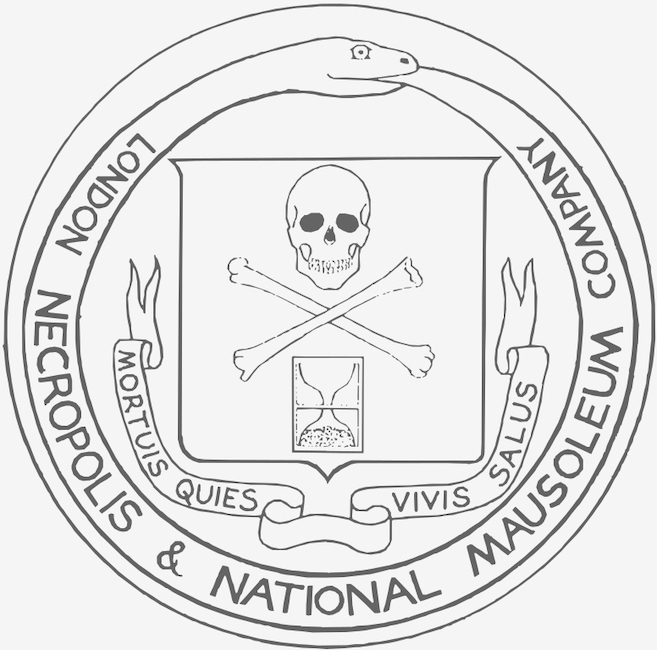

The same year brought the London Necropolis and National Mausoleum Act, which contracted with the London and South Western Railway Company to ferry the dead and their loved ones from central London to a vast new site at Woking, 20-odd miles away, comprising over 2,000 acres.

Thus the Necropolis Railway was born, bringing together two things at which the Victorians unarguably excelled: heavy industry and heavy mourning. The service started on 18 November 1854, running out of a purpose-built annex at Waterloo. It had two platforms, one for the living and one for the dead.

Five classes of funeral were available. Prices, based on four mourners each, ranged from £21, 14s for first class to £3, 9s for fifth, also known as a ‘Walking Funeral’. The journey took half an hour. It was said you could be there and back in two hours, with time for the interment included. Time, for the living, was still precious.

This is an extended version of a piece that first appeared in the November 2023 issue of History Today.

Like this? You can read more of Mathew’s History Today Months Past pieces here.

Leave a comment