On 3 April 1897, nineteen painters and sculptors met in a Viennese coffee house. Out of the meeting came a new arts movement, the Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs, better known as the Viennese Secession. At its head was a young Gustav Klimt.

Art in Vienna was controlled by the Künstlerhaus, the artists’ professional body. The Künstlerhaus was firmly embedded in the imperial establishment: its annual exhibition was opened by the emperor. It was this from which Klimt and his friends were seceding; their movement’s name derived from secessio plebis, the withdrawal of labour by the artisan class during the Roman republic in response to patrician abuses of power.

The Secession was a creative revolt; they sought what they called stilkunst – a complete aesthetic renewal. Bbut it was a pragmatic one too. The Künstlerhaus controlled not only which paintings were exhibited in Vienna, but which Viennese paintings could be exhibited abroad.

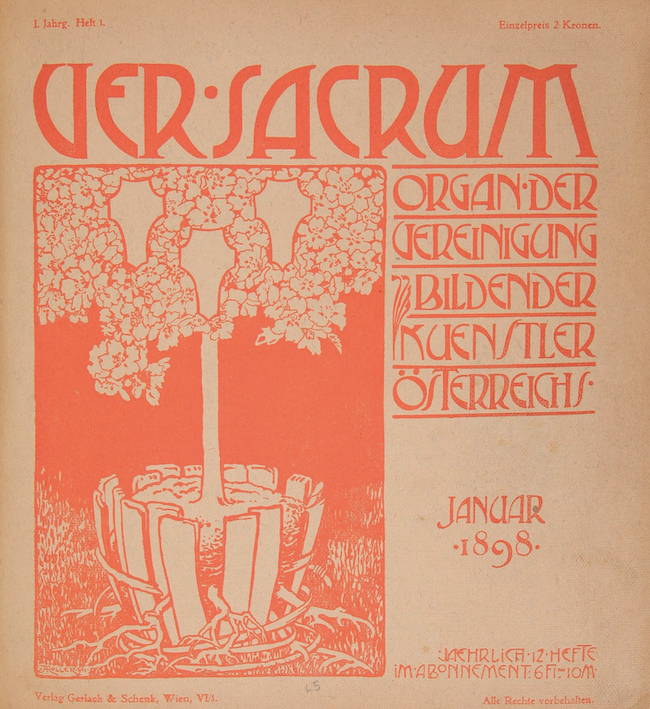

A magazine, Ver Sacrum – ‘Sacred Spring’ – was launched the following year. It too looked to Rome for its name, referencing an ancient pagan ritual of renewal. One issue was confiscated by the authorities because it “violated the sense of shame with its depiction of nudity”.

The Secessionists built an exhibition space too, which art critic Ludwig Hevesi promised would “break the chains and raise the dead from their graves”, heralding the dawn of a ‘Great Vienna’. The building had a mixed reception, however: locals called it ‘the house with the golden cabbage head’.

Ver Sacrum lost subscribers and folded in December 1903. Rebellion is addictive: in June 1905 Klimt and others split from the Secession leaving only a rump of realist artists behind.

This is an extended version of a brief piece that first appeared in History Today in April 2024.

Leave a comment