“It was a long hot summer.” Thus Lord Scarman begun his account of the small dispute at Grunwick, a film-processing company in north-west London, which escalated into one of the defining industrial conflicts of the late 1970s.

The dispute began with the sacking of a young worker, Devshi Bhudia, for slow work on Friday 20th August 1976. A handful of others walked out in protest, led by the 43-year-old Jayaben Desai, who quickly became the figurehead of the strike. Desai, like many of Grunwick’s employees, was a Gujarati woman from East Africa, forced to flee her home with tens of thousands of other Asians by anti-Asian policies, such as those of Idi Amin in Uganda, in the early 1970s.

Pay and conditions at Grunwick were poor. Desai was taking home £36 for a 50-hour week – around half the national average weekly wage. Overtime was compulsory; the basic weekly pay was between £25 and £30. The first year of work earned two weeks’ holiday the following year – which could not be taken in the summer months, the company’s busiest time. Staff had to ask permission to use the toilet.

Desai reportedly told her manager, Malcolm Alden: “What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. In a zoo there are many types of animal. Some are monkeys who dance to your tune; others are lions who can bite your head off. We are the lions, Mr Manager.” Alden later said all that really stuck in his mind was the phrase, “I want my freedom”.

The strikers contacted their local Citizens Advice Bureau, which put them in touch with Jack Dromey, then secretary of the Brent Trades Council, and the TUC. They joined a union, the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (Apex), now part of the GMB. This shifted the focus of the dispute towards broader issues of union rights and recognition. More joined the strike. Out of some 490 employees, 91 permanent staff and 46 student workers walked out.

Grunwick’s managing director George Ward, himself an Anglo-Indian immigrant, responded by sacking all the strikers. He was not opposed to union membership per se, he said. But he refused to negotiate with a union acting on behalf of his employees and was fearful that a ‘closed shop’ – under which all employees would be compelled to join the union – would be imposed. Closed shops, Ward thought, were “the ultimate affront to liberty”.

Apex took the dispute national. Roy Grantham, the union’s general secretary, denounced Grunwick as “a reactionary employer taking advantage of race and employing workers on disgraceful terms and conditions” in a speech to the annual TUC conference on 6 September. Post Office workers at the local sorting office refused to deliver to Grunwick; chemist shops, from which films and photographs were despatched and received, began to be picketed. Some 84% of Grunwick’s trade was mail order.

Apex approached Acas, the national conciliation service; Grunwick refused to participate and ignored its ruling. Instead, it commissioned two independent surveys of its employees’ views from Mori and Gallup. Both found overwhelming opposition to unionisation. The striking workers, having already been sacked, were not surveyed. Grunwick gave its employees pay rises of 15% and then another 10%.

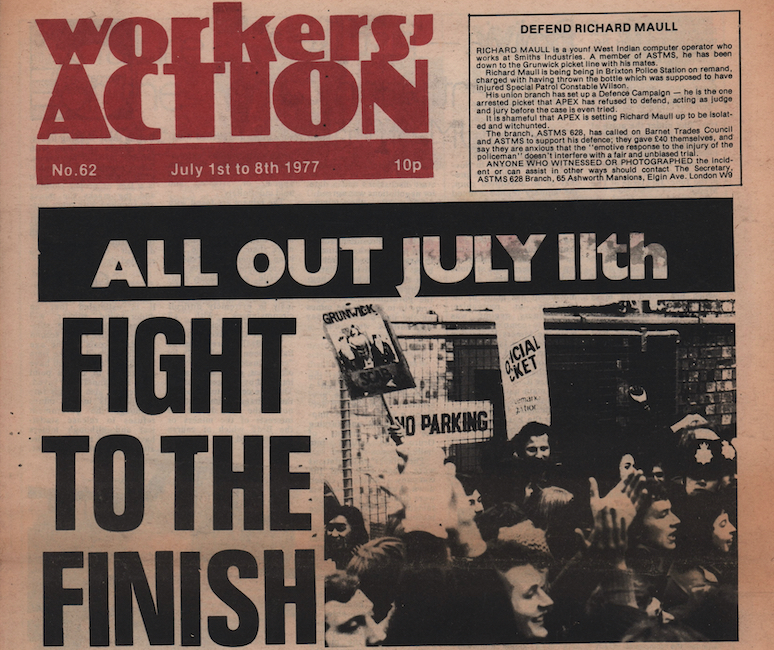

Faced with Grunwick’s resistance, the union called for a mass picket in the early summer of 1977. Supporters came in their thousands, peaking at around 20,000 on the union movement’s ‘National Day of Action’ on 11 July 1977. Policing was correspondingly heavy, involving up to 3,500 officers. In total there were some 550 arrests. There were hundreds of injuries among both police and protestors, but the injury that dominated the news coverage was a police officer hit in the head by a glass bottle: images of him lying motionless in a pool of blood as the conflict surged about him shocked many.

One young employee, Azadi Patel, reported being pelted with gravel as she walked her three-year-old son to childcare; she received phone calls threatening his kidnap if she didn’t join the strike. Someone painted the word ‘scab’ on her front door. Another young woman was told she would be beaten up. Strike organisers blamed outside elements for the violence; some suspected plain-clothes police officers set it in motion. One of Grunwick’s managers drove over Desai’s foot with his car and the police did nothing.

To Ward, it was the leadership of the trades union movement who formed “an arrogant and reactionary Establishment”. Its supporters practised “thuggery” against his employees, he said, many of whom “had been forced out of their former countries under the most harrowing of circumstances”. He thought much of the trouble was down to the involvement of the man he called Jackboot Dromey.

Dromey later wrote that it was ”the biggest mobilisation in British labour-movement history in support of fewer than 200 strikers”. It was, one activist told the Sunday Times, “the Ascot of the Left. It is essential to be seen here”. The protest drew figures as politically disparate as Shirley Williams, then a Cabinet minister in the Labour government, and Arthur Scargill, the leader of the Yorkshire miners, who brought 150 of his members with him to march in solidarity.

At the end of June 1977, the government asked Lord Scarman, a prominent lawyer, to lead an inquiry into the dispute. His report, at the end of August, recommended that Ward reinstate the strikers and recognise the union. Ward refused; the House of Lords backed him.

The strike ended in defeat on 14 July 1978 after some 670 days. Desai blamed the Labour government for failing to ensure the strikers won. But support from both the wider union movement and the government had weakened as the violence of the demonstrations had played out on the nightly news bulletins.

The dispute was a turning point in industrial relations. “The trades union movement… is fighting this one now not just against [Grunwick], but, in a sense, against the next Tory government,” wrote the Trotskyite Workers’ Action in July 1977. The Conservatives agreed. Its spokesman for industry Sir Keith Joseph called the dispute “a make or break point for British democracy, the freedoms or ordinary men and women”. Margaret Thatcher’s government, elected in 1979, outlawed secondary picketing – that is, picketing anywhere that is not your own place of work – in its 1980 Employment Act. It remains illegal.

But Grunwick was also the first time the union movement had thrown its weight behind immigrant workers. As recently as 1974 the Transport and General Workers’ Union had refused to support Asian workers striking for equal pay and conditions with their white colleagues at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester. “We have shown,” Desai said at the last meeting of her strike committee, “that workers like us, new to these shores, will never accept being treated without dignity or respect.”

This is a greatly extended version of a piece that first appeared in the August 2022 issue of History Today.

Like this? You can read more of Mathew’s History Today Months Past pieces here.

Leave a comment