As a child in the first years of the 20th century the great American film director Preston Sturges lived in a stylish apartment in Paris with his mother. An earphone hung beside the fireplace. He tried it; it seemed dead. Then one evening a family friend visited and, after dinner, sat in rapture, the earphone pressed to his ear. It was connected, Sturges discovered, to the Paris opera house and enabled people all over the city to listen to live performances.

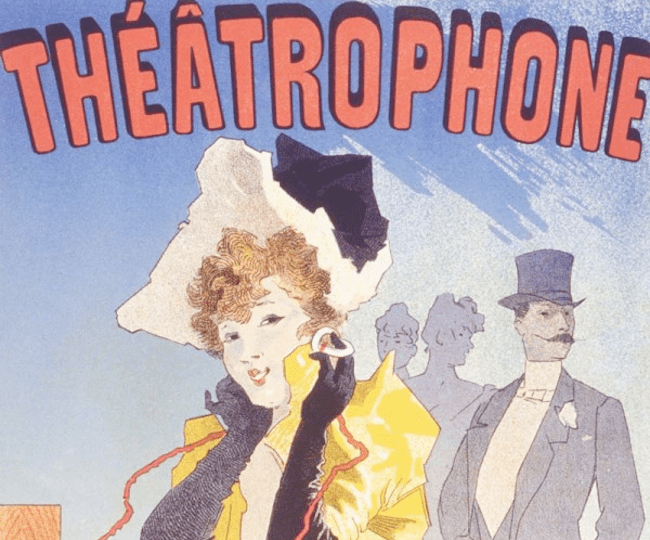

The théatrophone was the invention of the engineer Clément Ader, best remembered now as a pioneer of powered flight. It premiered at the vast international Exhibition of Electricity, which opened to the public in Paris on 11 August 1881 at the Palais de l’Industrie – in a “great blaze of splendour” a visiting British electrical engineer later recalled.

Two rooms, their walls heavily carpeted in an early attempt at soundproofing, were dedicated to Ader’s technology: in one, visitors could hear Racine’s Phèdre at the Comédie-Française; in the other, Gounod’s Le tribut de Zamora at the Palais Garnier. The technology was originally in stereo – or ‘perspective listening’ as it was called – but later reverted to mono. It was, The Times said, “the most marvellous thing of all” at the exhibition.

Théatrophone services sprang up in several European capital cities, among them Paris, London and Budapest. The technology did not survive the advent of radio, but one lingered on in Bournemouth until the death of its last two subscribers in 1937.

This piece first appeared in the August 2022 issue of History Today.

Like this? You can read more of Mathew’s History Today Months Past pieces here.

Leave a comment